This post continues the previous post, part 1 on scoring rules. However, today we will be more hands on, testing your skill of making good and well-calibrated predictions.

To this end, I will ask you several questions about numerical quantities and I would like to hear an answer stated as a belief interval. First, we consider scoring rules for intervals.

Interval Scoring Rules

Often the prediction or elicitation of a full probability distribution is cumbersome due to the many degrees of freedom a distribution has.

Therefore, in practice we can instead ask our model or users for intervals. This carries the implicit assumption of unimodal beliefs, which may not be satisfied in important tasks, but has the advantage of requiring only two numbers to be elicited.

Given an interval forecast \([L,U]\), where \(U > L > 0\), and \(x > 0\) is a realization, (Gneiting and Raftery, 2007) define the following interval scoring rule for \(\alpha \in (0,\frac{1}{2})\),

This is a proper scoring rule for intervals constructed from the sum of two quantile losses at the \(\alpha\)-quantile and the \((1-\alpha)\)-quantile. However, it has the problem that if the score is used in different contexts where the quantities \(x\) are of very different scales, then the resulting scores also carry this scale and are not comparable.

To achieve a scale-free interval scoring rule, we propose the following scale-free interval scoring rule.

The rule is negatively oriented, thus acting as a loss function. This scoring rule is proper and is minimized in expectation over \(X\) if we set \(L = F^{-1}(\alpha)\) and \(U = F^{-1}(1-\alpha)\) where \(F\) is the cummulative distribution function of \(X\) so that \(L\) and \(U\) become the \(\alpha\)-quantile and the \((1-\alpha)\)-quantile. (You can find a short proof that this is a proper scoring rule in an appendix to this article.)

Quiz

The following quiz tests your ability to make well-calibrated but uncertain assessments. (This also means that the quiz becomes somewhat pointless if you resort to Google or Wikipedia searches.) The quiz contains twelve items, and each item asks for a number, assuming there is a single true answer. Please pay attention to the units being asked for. Your knowledge regarding the different items is likely quite variable and for some questions you may have a good idea (your beliefs are concentrated), whereas for some other questions you may be more uncertain.

Because of this uncertainty the quiz does not ask you for your best guess but instead asks for an interval in an attempt to elicit your subjective beliefs. The lower number should be chosen such that you consider it 10 percent likely that the truth is below this number. The upper number is a 90 percent quantile and should be chosen such that there is a 10 percent chance that the truth is above this number.

For example, say the question is "Maximum horsepower of an 2015 Audi R8 car (horsepower)". Given my limited knowledge of cars I know that the Audi R8 is likely a quite powerful car so I would provide maybe an interval of 200 to 510. How I arrive at this is up to me, for example, I may consider that a car manufacturer may want to break the magic "500 horsepower" mark for marketing purposes. Fixing this interval, the truth is revealed. The truth is 570 horsepower, and the above scale-free interval loss would be 0.205.

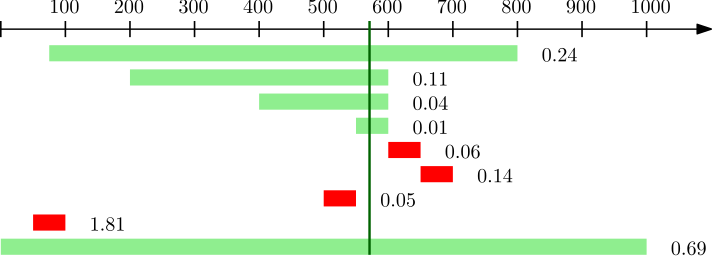

For the interval score a lower score is better, that is, the score is negatively-oriented and behaves like a loss function. Here is an illustration of different intervals and their scores for the example. I plot the true value 570 as a solid green vertical line, and the intervals are green if they cover the truth and red otherwise. The score is shown next to each interval.

Have fun, and feel free to comment or suggest new questions/answer in the comment field.

Based on my informal testing with a few volunteers, for the above questionaire the following seems like a reasonable subjective scale for the average score:

- \(0\) to \(0.1\), expert

- \(0.1\) to \(0.2\), proficient

- \(0.2\) to \(0.5\), good

- \(0.5\) to \(1.0\), medium

- above \(1\), fair

As for calibration, you should ideally have around eight to ten out of the twelve questions showing as green, because the quantile range should have 80 percent coverage. (Most persons who do not work with probability on a regular basis will have a lower coverage because of overconfidence.)

Acknowledgements. I thank John Winn for the original calibration experiment he conducted in 2014 which inspired this article, Tilmann Gneiting for commenting on the scale-free quantile score, Peter Gehler for feedback and providing further questions, Cheng Soon Ong for comments that improved clarity of the article, Ian Kash for explaining scoring rules, Christoph Dann and Juan Gao for feedback on the questionnaire.

Appendix: Propriety of the Scale-free Interval Scoring Rule

The following is a proof that the scale-free interval scoring rule is proper. We will use the result from (Gneiting and Raftery, 2007) and show that our scoring rule is a special case.

First, consider the general form of a scoring rule for an \(\alpha\)-quantile from Theorem 6 in Gneiting and Raftery; for a choice \(r\) and realization \(x\) this takes the form

Gneiting and Raftery show that for any nondecreasing function \(s\) and an arbitrary function \(h\) this yields a proper scoring rule for quantiles. Infact, it is known that any proper scoring rule for quantile has to be of the form \((\ref{eqn:Squantile})\), see Theorem 3.3 in (Gneiting, 2009). In the Gneiting and Raftery JASA paper the authors propose the choices \(s(y)=y\) and \(h(y)=-\alpha y\). But here, in order to achieve a scale-free rule we propose to use

We obtain the specialization of \((\ref{eqn:Squantile})\) as

Because \(s\) is a non-decreasing function this is a proper scoring rule for quantiles. This quantile loss looks as follows (compare to the check loss figure earlier), for different quantiles (\(x=5\) is the sample realization, and the horizontal axis denotes our quantile estimate).

The expected risk plot has a different shape compared to the check loss that we have seen earlier, but note that the minimizer again corresponds to the right quantiles of the \(N(5,1)\) belief distribution.

By using Corollary 1 in (Gneiting and Raftery, 2007) the sum of multiple quantile scoring rules remains a proper scoring rule. To obtain a scoring rule for intervals we use the \(\alpha\)-quantile and the \((1-\alpha)\)-quantile to obtain (after some rewriting of terms)